1. Executive Summary: Key Takeaways for 2026

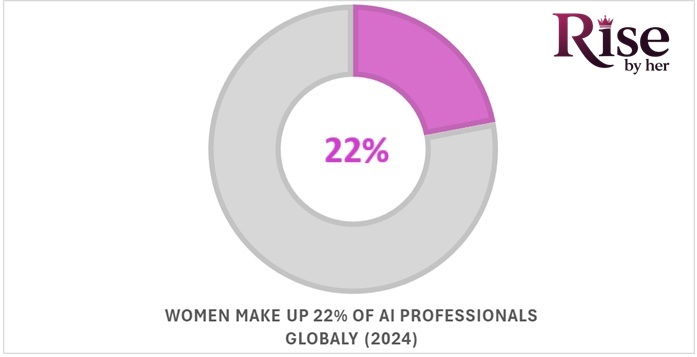

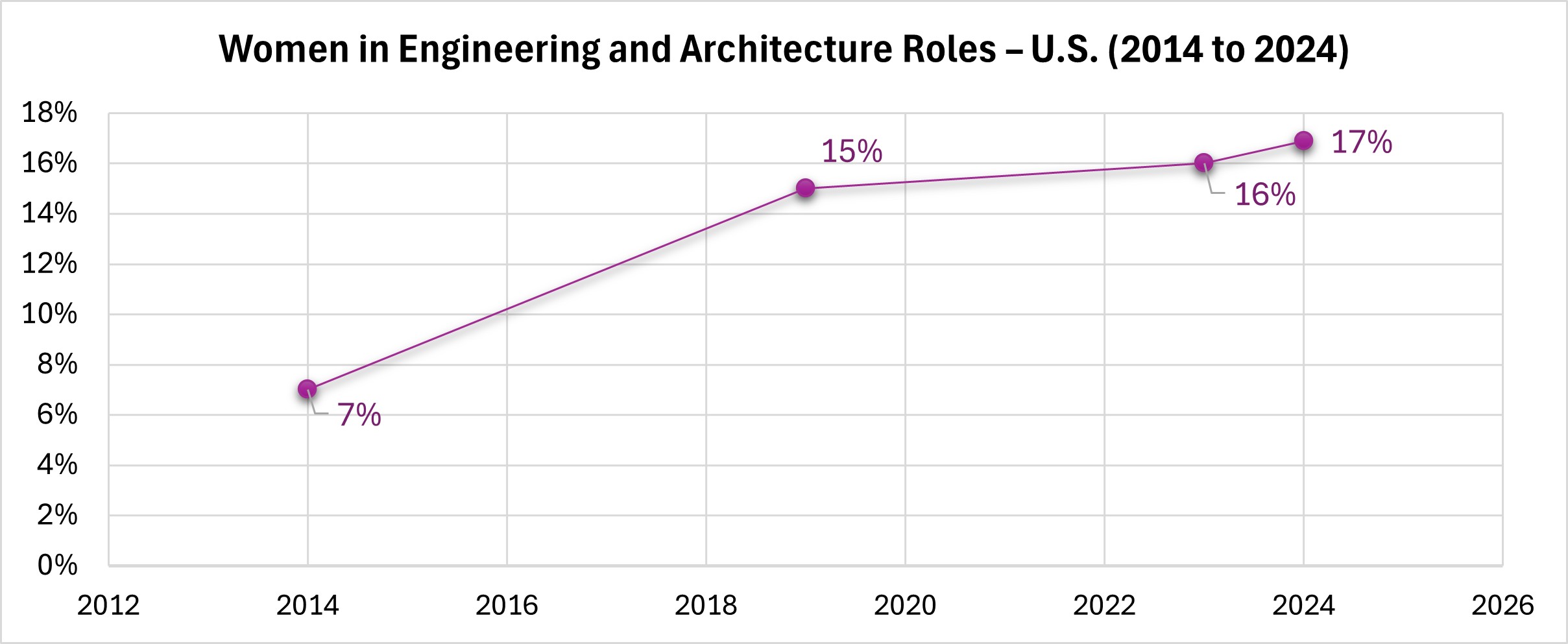

Despite decades of concerted efforts and growing advocacy, women continue to be significantly underrepresented in the field of engineering. Current data from 2023-2024 indicates that women constitute only approximately 16% to 17% of the engineering workforce in the United States.1 This figure stands in notable contrast to their representation in the broader STEM workforce, where women comprise between 26% and 34% of professionals.1 Globally, the disparity is similarly pronounced, with women making up just 28% of the overall STEM workforce and a mere 22% of artificial intelligence (AI) professionals in 2024.6

While historical trends reveal an increase in women earning engineering degrees, the rate of growth has slowed considerably since the 1990s.5 This deceleration suggests that achieving genuine gender parity in engineering will require many more decades if current trajectories persist.8 A critical examination of the data points to a persistent “leaky pipeline” phenomenon, particularly post-graduation. A substantial number of women depart the engineering field by mid-career, driven by factors beyond initial interest, such as challenging workplace cultures, insufficient flexibility, and ongoing pay disparities.8 This trend underscores the urgent need for systemic transformations within the industry, moving beyond interventions focused solely on individuals to address deeply ingrained structural and cultural barriers.

The pronounced difference in representation between engineering and other STEM fields suggests that engineering faces unique and potentially more deeply entrenched obstacles to gender equity. While general STEM diversity initiatives are valuable, they may not be sufficient for the specific challenges within engineering. This indicates that discipline-specific strategies are crucial, addressing the particular cultural perceptions, historical biases, and educational pathways inherent to engineering. The challenge extends beyond merely increasing the number of women in STEM to specifically increasing and retaining women within engineering.

Furthermore, the slow pace of progress, despite decades of increased awareness and numerous initiatives, presents a paradox. Organizations have raised concerns about the lack of representation for years, and events like International Women in Engineering Day (INWED) aim to highlight the issue.3 Yet, this sustained attention has not translated into rapid, systemic change. This suggests that the barriers are deeply ingrained that require more than just awareness campaigns or isolated programs. It points to a need for sustained, comprehensive, and potentially disruptive strategies that challenge the foundational aspects of the engineering profession and its culture.

Despite these persistent challenges, there is a discernible forward momentum for 2026. Various organizations and industry bodies are demonstrating a clear commitment to accelerating progress. Initiatives such as the 50K Coalition aim to produce 50,000 diverse engineering graduates annually by 2025.12 Additionally, some leading firms have established ambitious targets for gender parity in recruitment and management roles by the same year.11 These concrete goals, coupled with a growing recognition of the compelling business case for diversity, offer a hopeful outlook for cultivating a more inclusive future in engineering.

2. Current Landscape: Women in Engineering by the Numbers (Global & US)

The current state of women’s representation in engineering reveals a complex landscape, characterized by persistent underrepresentation, significant disciplinary variations, and notable regional disparities. Understanding these numerical realities is fundamental to identifying where interventions are most needed.

Overall Representation in Engineering

In the United States, the presence of women in engineering and architecture occupations remains notably low. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that women constituted approximately 16% of this combined workforce in 2023.1 This figure represents a modest increase from 15% in 2019.2 More broadly, other reports from 2024 place women’s representation in the engineering workforce at around 16.9%.4 While this is a substantial improvement from the 7% recorded in 2014, when the inaugural Women in Engineering Day was celebrated, it still signifies a considerable gender gap that requires ongoing attention.4

Globally, women comprise a smaller proportion of the STEM workforce compared to non-STEM fields. In 2024, only 28.2% of the global STEM workforce was female, in stark contrast to the 47.3% female representation in non-STEM sectors, according to the World Economic Forum.6 Within global research positions, women hold less than one-third of the roles.7

Regional variations in the representation of women in science and engineering research are significant. In 2022, women accounted for 31.1% of R&D personnel worldwide, an increase from 29.4% in 2012.7 Some regions demonstrate near gender parity among R&D researchers, such as Central Asia (50.8% in 2022) and Latin America and the Caribbean (45.3%). Conversely, regions like East Asia and the Pacific (26.3%) and South and West Asia (26.9%) exhibit severe gender imbalances.7 At the country level, only Argentina (53.6%) and Malaysia (53.5%) achieved gender parity in R&D personnel, whereas countries like Congo and India reported less than 19% female representation in the last five years.7

Within Europe, similar patterns of underrepresentation are observed. In France, women constituted only 28% of students in engineering schools in 2023.14 Alarmingly, the share of women graduating in engineering, construction, and manufacturing in France saw a 12% decline between 2015 and 2021, dropping from 26.7% to 23.6%, while the European average remained stable at approximately 28%.14 In the United Kingdom, women make up 16.9% of the engineering and technology workforce, compared to 56% in other occupations.15

Representation by Engineering Discipline

The gender gap in engineering is not uniformly distributed across all disciplines; rather, it varies significantly by specialization.1 In 2020, women achieved notable representation in biomedical engineering, earning half of all bachelor’s degrees in this field.8 This indicates a strong presence and interest in this specific area of engineering.

However, their representation is considerably lower in other foundational engineering disciplines. Women comprise 35% of environmental engineers, 18% of chemical engineers, 10% of electrical engineers, and a mere 9% of mechanical engineers.16 These disciplinary distributions have remained remarkably consistent over the past two decades. For example, women earned 37% of bachelor’s degrees in chemical engineering in 2002 and 37.7% in 2020, while in mechanical engineering, the percentages were 14% in 2002 and 16.5% in 2020.8 This stability underscores a persistent pattern of disciplinary segregation within the field.

The stark contrast in female representation across different engineering disciplines, with fields like biomedical engineering approaching parity while mechanical and electrical engineering lag significantly, is a critical observation.8 The fact that these proportions have remained “quite stable” over the last 20 years suggests that the challenge is not simply about attracting women to engineering generally, but about deeply ingrained perceptions and pathways within specific sub-disciplines.8 This implies that certain fields are perceived as more “masculine” or less aligned with women’s interests, potentially leading to self-selection or subtle discouragement. Effective interventions must therefore move beyond generic recruitment to address the specific cultural narratives, curriculum framing, and availability of role models within each engineering discipline. For instance, highlighting the communal and societal impact aspects of mechanical or electrical engineering could resonate more with women who are often drawn to fields perceived as helping others.17

The overall global picture of women’s underrepresentation in STEM and engineering is undeniable.6 However, the existence of specific regions like Central Asia (50.8% female R&D researchers) and Latin America and the Caribbean (45.3%) exhibiting near gender parity presents a compelling contrast.7 This significant regional variation challenges the notion of universal, intractable barriers to women’s participation. It suggests that particular cultural, educational, and policy contexts can either dramatically accelerate or hinder progress. The successes in certain regions indicate that parity is achievable and offer potential blueprints for other parts of the world. This implies that efforts to increase women in engineering should adopt a “tailored solutions” approach 6, learning from successful regions and adapting strategies to country-specific challenges and cultural nuances. Localized research into the drivers of success in high-parity regions is critical to inform these strategies.

The following table provides a concise overview of women’s representation across key engineering disciplines:

| Discipline | Percentage of Women (approx. 2020-2023) |

| Overall Engineering Workforce (US) | 16-17% 1 |

| Biomedical Engineering (B.S. degrees) | 50% 8 |

| Environmental Engineering | 35% 16 |

| Chemical Engineering | 18% (workforce), 37.7% (B.S. degrees 2020) 8 |

| Electrical Engineering | 10% 16 |

| Mechanical Engineering | 9% (workforce), 16.5% (B.S. degrees 2020) 8 |

3. The Pipeline: From Education to Early Career

Analyzing the educational and early career pipeline for women in engineering reveals both historical progress and areas of persistent challenge, particularly concerning retention and the pace of change.

Trends in Engineering Degrees Awarded to Women

Over the long term, there has been a substantial increase in the proportion of engineering degrees awarded to women across all academic levels—bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral. For instance, in 1954, women earned less than 1% of engineering Bachelor of Science degrees, a figure that climbed to 23% by 2020.8 However, the most significant surges in these numbers occurred in the 1970s and 1980s. Since 1990, the growth rate has slowed considerably.5 This deceleration indicates that at the current pace, achieving true gender parity in engineering degree attainment will extend over many more decades.8

The current degree landscape continues to show a notable gender gap. In 2023, men were awarded 69% of engineering bachelor’s degrees.17 Furthermore, data suggests that enrollment among women in STEM-related university programs has largely stagnated over the past decade.6 This stagnation is also reflected in persistence rates within STEM majors: in the US, men are considerably more likely to continue pursuing a STEM major (65.0%) compared to women (48.0%).19 This suggests that while women may initially enter STEM fields, a significant proportion do not complete their degrees in these areas.

A key initiative aimed at addressing this pipeline challenge is the 50K Coalition. This collaborative effort has a national objective to produce 50,000 diverse engineering graduates annually by 2025. Currently, of the approximately 93,000 bachelor’s degree engineers graduating each year in the US, only 30,000 are from underrepresented minority populations or are women.12

Representation in Faculty Positions

| Category | Percentage of Women | Context/Details |

| Overall Engineering Faculty Positions | 9.25%8 | 2002 |

| Overall Engineering Faculty Positions | 18.5%8 | 2021 |

| Full Professors of Engineering | 13.6%8 | 2020 |

| Assistant Professors of Engineering | 25.4%8 | 2020 |

| Tenured Female Professors in Engineering and Technology | 17.9%14 | European Union (2022) |

Transition Rates from Academia to the Workforce

The initial transition from academia into the engineering workforce presents an interesting dynamic. In 2021, 53.4% of women with engineering degrees who had graduated within the last one to five years were working in engineering roles, a figure slightly higher than their male counterparts (49.3%).9 This suggests that women are successfully entering the field immediately after graduation.

However, the overall percentage of employed engineers who are women has increased steadily but slowly over the past 25 years, growing from less than 10% in 1993 to approximately 14% in 2019.8 This figure is notably lower than their share of engineering degrees, which stood at 23% in 2020.8 This discrepancy indicates that while women are graduating with engineering degrees and initially entering the workforce, a significant “leak” in the pipeline occurs at later career stages.

The data reveals a significant increase in women earning engineering degrees over the decades 8, and even a slightly higher initial retention rate for women in engineering roles 1-5 years post-graduation compared to men.9 Yet, the overall percentage of employed female engineers, around 14-16%, remains notably lower than their proportion of degrees awarded, which was 23% in 2020.2 This pattern suggests that the primary attrition point in the pipeline has shifted. It is no longer predominantly at the entry into university programs or even immediately upon graduation. Instead, a more significant loss occurs later, as women progress through their careers. The initial positive retention rate for recent graduates quickly diminishes over time, as evidenced by the sharp drop in women remaining in engineering roles 11-15 years post-graduation.9 This observation fundamentally shifts the focus of intervention. While early exposure and academic support remain important, the most critical area for impact in 2025 and beyond must be on retaining and supporting career progression for women already in the workforce, particularly those in mid-career stages. Strategies must address the systemic and cultural factors that cause women to leave after gaining valuable experience and qualifications, rather than solely focusing on increasing initial numbers.

Furthermore, while women’s share of engineering degrees saw “significant increases” in the 1970s and 1980s, the growth has “slowed considerably since 1990”.8 Similarly, female STEM representation “stagnated” since 2000, rising only 1% in 12 years.5 This long-term deceleration, despite ongoing efforts and awareness, indicates that the “easy wins” from early diversity initiatives have been achieved. The remaining barriers are likely more deeply embedded and resistant to change, requiring more profound, structural interventions rather than incremental adjustments. It suggests that the initial momentum, driven by breaking overt barriers, has hit a plateau where more subtle, systemic issues prevail. Continuing with the same strategies that yielded success in previous decades will likely result in continued slow progress. Achieving significant shifts by 2025 and beyond necessitates a radical rethinking of approaches, focusing on dismantling deeply entrenched biases, transforming workplace cultures, and addressing systemic inequities that have proven resistant to past efforts. This calls for a more aggressive, comprehensive, and potentially uncomfortable examination of the engineering ecosystem.

4. Challenges in Retention and Progression: Why Women Leave

The “leaky pipeline” in engineering is not primarily an issue of attracting women to the field, but rather a significant challenge in retaining them, particularly at mid-career stages. This section delves into the multifaceted reasons behind women’s departure, including the persistent gender pay gap, unwelcoming workplace cultures, and barriers to career advancement.

Mid-Career Attrition Rates

A substantial challenge is the high attrition rate of women in engineering careers. Overall, approximately 50% of women leave the engineering field by the middle of their careers.10 This trend is strikingly evident when examining retention over time: in 2021, while 53.4% of women with engineering degrees who graduated within the last 1 to 5 years were working in engineering roles, this figure plummeted to only 26.8% for women who completed their degrees 11 to 15 years prior.9 In contrast, 41% of male engineers from the same cohort remained in the field.9 In the broader tech industry, half of all women reportedly leave by age 35, and women are approximately 45% more likely to leave the industry than men.20

Key Reasons for Leaving

Several interconnected factors contribute to women’s departure from engineering:

- Workplace Culture: A significant proportion of women, 30%, cite issues with workplace culture as a primary reason for leaving.10 Research frequently describes a “bro culture” prevalent in many high-tech and engineering firms, where sexist behavior, indignities, microaggressions, and unequal treatment are tolerated.8 A 2024 UNESCO report highlighted that over a third of women reported sexism, harassment, or gender-based violence as a top challenge.22 Many women report feeling isolated, often being the sole female in their department.21

- Work-Life Balance and Family Responsibilities: Work/family conflict is a leading explanation for women leaving engineering, as they often find the demanding time commitments difficult to reconcile with domestic responsibilities.8 Flexible work options are frequently unavailable, disproportionately affecting women who often bear the dual burden of professional and family care.21 Women tend to value work-life balance significantly more than men, a factor that often influences their career choices.10

- Lack of Career Progression and Opportunities: Women frequently report unmet achievement needs, a perceived absence of pay raises or promotion opportunities, and feeling “stalled” or “stuck” in their careers.9 One study indicated that 40% of respondents felt this way.21 Women may also find themselves moved into less technical roles, such as marketing, or assigned “office housework” tasks that do not contribute to career advancement.10

- Perception of Engineering as “Masculine” and Bias: Engineering is widely perceived by both children and parents as a masculine field, which can deter girls from considering it and affect their sense of belonging and aspirations within the profession.8 The association of engineering with “brilliance,” a quality often more attributed to boys, also steers girls away.8 Bias can manifest in hiring and promotion processes, with some studies suggesting women face more intense scrutiny during interviews or are less likely to receive job offers.8

The Gender Pay Gap in Engineering

The gender pay gap remains a significant and persistent issue within engineering. In March 2024, the gender pay gap in Engineering was recorded at 9.5%, meaning that women typically earned 90 cents for every dollar earned by men.24 While this represents a marginal improvement of 0.9 percentage points compared to March 2022, it underscores the ongoing disparities in compensation.24 Across STEM fields more broadly, women earned 87 cents for every dollar men earned in March 2024.24 Globally, women earned approximately 83 cents for every dollar earned by men in 2024.25 In the United States, women earned 83.6% of what men earned in 2023.26

The pay gap is not solely a matter of unequal pay for the same role; it is often a symptom of deeper systemic issues related to career trajectory and opportunity. Research indicates that nearly 80% of the US gender pay gap is driven by women having “flatter work experience arcs,” accumulating less time on the job, and being more likely to switch to lower-paying occupations.18 This results in an average of half a million dollars in lost earnings per woman over a 30-year career, highlighting the profound long-term economic impact of these career divergences.18

The various reasons for women leaving engineering are not isolated but rather intersect and reinforce each other.8 For instance, a “bro culture” might lead to women being assigned “office housework” rather than high-visibility projects, which in turn limits promotion opportunities and contributes to a flatter career arc and a wider pay gap.10 Simultaneously, the disproportionate burden of family responsibilities can make it harder to endure an unsupportive environment or to take on roles with long, inflexible hours.21 This interconnectedness means that a piecemeal approach to solutions, such as focusing solely on pay or just on mentorship, will be insufficient. True retention requires a holistic strategy that addresses the entire ecosystem of challenges in an integrated manner. Organizations must recognize that these issues are deeply intertwined and address them comprehensively.

Furthermore, while the immediate pay gap (e.g., 90 cents for every dollar) is a direct concern 24, the finding that nearly 80% of the

total gender pay gap is driven by women’s “flatter work experience arcs,” including less time on the job and movement into lower-paying occupations, reveals a more profound issue.18 This indicates that the pay gap is not just about unequal pay for the same work, but a symptom of deeper systemic issues related to career trajectory and opportunity. Women are not merely paid less for the same work; they are often steered towards, or compelled into, career paths that inherently pay less or offer fewer advancement opportunities due to a combination of workplace culture, lack of flexibility, and implicit biases. The “lost earnings” over a career, amounting to half a million dollars, highlight the profound long-term economic impact of these systemic issues.18 Addressing the gender pay gap effectively therefore requires more than just salary audits. It demands a critical examination of career pathways, promotion criteria, access to high-value projects, and the provision of truly flexible work arrangements that do not penalize career progression. It also implies a need to challenge the societal division of labor that often places a disproportionate burden of family care on women, influencing their career choices and time commitment.

A seemingly contradictory finding is that despite high attrition rates, women engineers who remain in the field report high levels of job satisfaction (91.8% in 2021), mirroring their male counterparts.9 This observation suggests that women are not leaving engineering because they dislike the

work itself or the field of engineering. Instead, they are departing due to dissatisfaction with the conditions surrounding the work—the unwelcoming culture, lack of support, work-life conflict, and systemic barriers that make it untenable to continue, even if they enjoy the technical aspects of their jobs. The problem is not a lack of passion for engineering among women, but a failure of the engineering environment to retain them. This reframes the challenge from one of “fixing women,” such as making them more interested or confident, to one of “fixing the system”.8 Interventions must focus on transforming the workplace environment to be more inclusive, supportive, and flexible, ensuring that women who are satisfied with their engineering work are not forced out by external pressures or hostile conditions. This reinforces the need for cultural and structural changes over individual-focused programs.

The following table summarizes the gender pay gap in key STEM sectors:

| Sector | Gender Pay Gap (March 2024) | Women Earn for Every $1 Men Earn |

| Engineering | 9.5% 24 | $0.90 24 |

| Science | 13.1% 24 | $0.87 24 |

| IT | 7.0% 24 | $0.93 24 |

| Overall US Workforce (2023-2024) | 16.4% (83.6 cents) to 17% (83 cents) 25 | $0.83 – $0.836 25 |

5. Addressing the Gap: Initiatives and Future Opportunities for 2026 and Beyond

Addressing the persistent gender gap in engineering requires a multi-pronged approach that combines effective interventions with strong industry commitments and a fundamental shift towards systemic change. The outlook for 2025 and beyond is shaped by a growing understanding of what works and a collective resolve to implement lasting solutions.

Effective Interventions and Programs

Several strategies have proven effective in supporting women in engineering:

- Mentorship and Sponsorship: Connecting aspiring scientists, innovators, and engineers with mentors who have navigated similar challenges provides practical guidance and confidence.6 Studies have demonstrated that mentorship programs can improve promotion and retention rates for women and minorities by 15% to 38%.6 Crucially, there is a growing call for “sponsorship, not just mentorship,” where advocates actively champion women’s careers and create opportunities for advancement.4

- Targeted Initiatives and Funding: Well-funded, sustained programs, such as the NSF-ADVANCE initiative designed to increase female faculty in science and engineering, have largely succeeded. Their success is attributed to factors like senior administrative support, institutional champions, collaborative leadership, and widespread participation.8 Similarly, the Global Engineer Girls (GEG) program has proven effective, supporting over 1,200 students and providing employment opportunities across various countries.6

- Fostering Inclusive Environments: Creating nurturing affinity spaces, implementing inclusive instructional practices, and reforming institutional norms are key strategies highlighted in recent literature.17 This includes encouraging open communication, establishing rotational leadership roles, developing mentorship programs, celebrating diverse cultural events, and setting clear guidelines for respectful behavior and conflict resolution.2

- Flexible Work Arrangements and Support: To mitigate retention challenges, particularly for women in mid-career (aged 35-64), more companies are adopting flexible shift patterns, career returner programs, and structured career progression plans.11 Parental leave policies that support both parents are also considered vital for retaining women in the workforce.2

- Challenging Stereotypes and Biases: Interventions at the undergraduate level that frame engineering as a field that is both communal and helps others can significantly increase women’s interest and confidence, as these qualities are often perceived to align with women’s values.17 Organizations are also advised to use inclusive language in job descriptions, avoid gendered terminology, and implement blind resume screening to minimize unconscious bias during the hiring process.2

Industry and Organizational Commitments for 2026

The year 2025 is marked by several concrete commitments from industry leaders and organizations:

- The 50K Coalition: This collaborative initiative, comprising over 40 organizations, has set an ambitious national goal: to produce 50,000 diverse engineering graduates annually by 2025.12 This directly addresses the imperative to diversify the talent pipeline at the graduation stage.

- Corporate Targets: Several leading engineering firms are establishing specific goals for 2026. One prominent firm is targeting 50/50 gender parity in early careers recruitment, aiming to cultivate an innovative and diverse culture. Another national firm has set a goal for 35% female representation among its management by 2025.11 These specific targets signify a shift from generic statements to measurable commitments.

- Awareness and Collaboration: The 2025 theme for International Women in Engineering Day (INWED), #TogetherWeEngineer, will underscore the importance of collaboration and inclusion in shaping the industry’s future.11 This reflects a growing understanding that collective action is essential for meaningful progress.

- Active Recruitment and Support: Companies are actively recruiting women by providing flexible working arrangements, comprehensive training and development programs, and fostering inclusive workplace cultures.11

The Importance of Systemic Change and Collaboration

Recent research increasingly emphasizes that addressing underrepresentation demands a multifaceted approach that extends beyond merely improving math skills or individual confidence. It necessitates understanding intersectional experiences and fundamentally transforming the masculine and at times biased culture prevalent in engineering workplaces.8 The focus is shifting towards comprehending and dismantling systemic issues and barriers encountered by underrepresented groups to promote equitable opportunities.3 This includes actively engaging men in the change process, as many may not perceive their institutions as sexist.8 Public-private-philanthropic partnerships are recognized as crucial for delivering large-scale outcomes in encouraging more women into STEM fields.6

Earlier research and interventions often focused on individual-level deficits or encouragement for women, such as improving math confidence or providing role models.8 However, recent literature, particularly from 2024, explicitly highlights a critical shift towards addressing “systemic obstacles” and “cultural/structural shifts”.3 This evolution in thinking acknowledges that the problem is not inherent to women’s capabilities or interests, but rather lies in the environment and structures of the engineering profession itself. It implies that superficial programs or individual “fixes” are insufficient. Real progress requires a deep overhaul of institutional practices, challenging ingrained biases, and transforming the “masculine culture”.8 This means that organizations must move beyond token gestures and implement comprehensive, top-down and bottom-up strategies that fundamentally alter hiring processes (e.g., blind screening, standardized interviews), promotion pathways (e.g., clear rubrics, diverse panels), and workplace norms (e.g., flexible work, anti-harassment policies). It also underscores the necessity of engaging male allies, as systemic change cannot occur without the active participation and buy-in of the dominant group.8

The repeated emphasis that gender-diverse teams are “more profitable and productive” and “more likely to introduce new innovations” underscores a critical point.2 Diversity is presented not just as a moral good but as a “business necessity”.2 This framing moves beyond corporate social responsibility to a clear competitive advantage. Companies that fail to attract and retain women are not just missing out on talent; they are actively hindering their own innovation capacity, problem-solving efficiency, market understanding, and ultimately, financial performance. The data quantifies this, showing that companies with over 30% female representation are significantly more likely to financially outperform others.2 This provides a powerful economic argument for investment in diversity initiatives. For leadership, it transforms diversity from a compliance issue or a “nice-to-have” into a core strategic imperative for sustained growth and market leadership in a rapidly evolving global economy. It implies that organizations ignoring gender diversity are not merely stagnant but are actively losing ground to more inclusive competitors.

While mentorship is frequently mentioned as a beneficial tool for women’s success 6, one source explicitly calls for “creating sponsorship, not just mentorship”.4 Another notes that 83% of women in SET jobs lacked sponsors.21 This distinction is crucial. Mentorship typically involves providing advice, guidance, and support. Sponsorship, however, implies active advocacy, where a senior leader uses their influence, network, and political capital to champion an individual, open doors, and actively promote their career advancement. In male-dominated fields where informal networks often exclude women 10, sponsorship is vital for breaking through the “glass ceiling” and accessing senior roles. For women to move beyond mid-level roles and into leadership, they need more than just guidance; they need powerful allies who will actively invest in their careers and create opportunities that might not otherwise be accessible. This means organizations need to formalize sponsorship programs and encourage senior leaders to proactively identify and champion high-potential women, ensuring they are considered for leadership roles and critical projects. This represents a higher-level intervention that directly addresses systemic barriers to advancement.

Benefits of Diversity

The case for closing the gender divide in STEM is compelling. Gender-diverse teams are demonstrably more profitable and productive; companies where female representation exceeds 30% are significantly more likely to financially outperform those with less.2 Gender-diverse R&D teams also show a greater propensity to introduce new innovations into the market over a two-year period.6 Diversity in engineering enhances creativity, promotes out-of-the-box thinking, leads to a better understanding of diverse customer needs, increases employee engagement and retention, strengthens company reputation, and enhances global competitiveness.2 Ultimately, investing in women in STEM leads to faster innovation and more effective problem-solving, particularly in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.6

The following table highlights key goals and projections for women in engineering for 2025:

| Goal/Projection | Target Date | Source/Context | Significance |

| 50,000 diverse engineering graduates annually | By 2025 | The 50K Coalition 12 | Aims to significantly increase the overall pool of diverse talent, including women, entering the engineering workforce. |

| 50/50 gender parity in early careers recruitment | By 2025 | A prominent UK engineering firm (implied: Lanes Group) 11 | Focuses on balancing the entry-level pipeline, crucial for long-term representation and fostering an innovative culture. |

| 35% female representation among management | By 2025 | A national UK firm (implied: Lanes Group) 11 | Addresses the “leaky pipeline” at higher career stages, promoting women into leadership and decision-making roles. |

| International Women in Engineering Day (INWED) theme: #TogetherWeEngineer | 2025 | INWED 11 | Raises global awareness and emphasizes collective action, collaboration, and inclusion as key drivers for future progress. |

6. Conclusion: Engineering a More Inclusive Future

The analysis of 2025 women in engineering statistics reveals a landscape of gradual progress alongside persistent challenges. While the presence of women in engineering has grown significantly over the decades, their representation remains notably low, particularly in core disciplines and senior leadership roles. The pace of this progress has decelerated in recent decades, indicating that the initial gains from breaking overt barriers have plateaued. A critical understanding emerging from the data is that the “leaky pipeline” is now predominantly a mid-career retention challenge, driven by systemic issues such as unwelcoming workplace cultures, a lack of flexibility, and persistent pay disparities, rather than merely a lack of initial interest or academic capability among women.

The imperative for greater gender diversity in engineering extends far beyond a matter of fairness; it is a critical driver of innovation, profitability, and problem-solving efficiency. Companies with greater female representation demonstrably outperform their less diverse counterparts financially, and gender-diverse R&D teams are more likely to introduce novel innovations into the market.2 A world that strategically invests in women in STEM will be a world that innovates faster and solves complex problems more effectively, a crucial advantage in the evolving landscape of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.6

Moving forward into 2025 and beyond, the path to a more inclusive engineering future requires a fundamental shift in approach. The focus must transition from “fixing women” to “fixing the system,” advocating for comprehensive, systemic changes across the entire industry. This necessitates continued and expanded efforts in mentorship, and crucially, a greater emphasis on sponsorship, where senior leaders actively champion and create opportunities for women. Tailored interventions that address specific disciplinary and regional disparities are also vital, alongside robust public-private-philanthropic partnerships to achieve large-scale outcomes.4

Creating truly inclusive work environments must be a priority, implemented through flexible policies, equitable career pathways, and the active challenging of biases and stereotypes at all levels.2 The importance of collective action is underscored by initiatives like the 2025 INWED theme, #TogetherWeEngineer, and the specific, measurable goals set by organizations for 2025, such as the 50K Coalition’s target for diverse engineering graduates and firms’ commitments to gender parity in recruitment and management.11

While the challenges are substantial and deeply embedded, the growing commitment and understanding within the industry offer a hopeful outlook. The ongoing efforts and concrete 2025 targets signal a strong resolve to make engineering a more accessible, supportive, and rewarding career for women. This concerted push towards a more equitable landscape will ultimately lead to a more innovative, resilient, and prosperous future for the engineering sector and society as a whole.

Works cited:

- Infographic: Women In Engineering 2024 – ASME, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.asme.org/topics-resources/content/infographic-a-snapshot-of-women-in-engineering-today

- DEI Practices In The Engineering Industry & Its Importance – Exude Human Capital, accessed July 17, 2025, https://exudehc.com/blog/dei-engineering/

- Equality, diversity, and inclusivity in engineering, 2013 to 2022: a review, accessed July 17, 2025, https://raeng.org.uk/media/pitehtfm/equality-diversity-and-inclusivity-and-engineering-2013-2023-a-review.pdf

- Women in Engineering Day 2025: Driving Change That Counts, accessed July 17, 2025, https://mepca-engineering.com/women-in-engineering-day-2025-driving-change-that-counts/

- 100+ Women in STEM Statistics 2025 – AIPRM, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.aiprm.com/women-in-stem-statistics/

- Women in STEM: Using reskilling to address the gender gap | World Economic Forum, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/01/why-it-s-time-to-use-reskilling-to-unlock-women-s-stem-potential/

- Global STEM Workforce – Society of Women Engineers, accessed July 17, 2025, https://swe.org/research/2025/global-stem-workforce/

- Women in Engineering: Analyzing 20 Years of Social Science … – SWE, accessed July 17, 2025, https://swe.org/magazine/lit-review-22/

- Retention in the Engineering Workforce – Society of Women Engineers – SWE, accessed July 17, 2025, https://swe.org/research/2023/retention/

- Study Shows Almost Half Of Female Engineers Leave The Field By Mid-Career, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.texasstandard.org/stories/study-shows-almost-half-of-female-engineers-leave-the-field-by-mid-career/

- Women in Engineering 2025: Key Trends and Future Opportunities – Lanes Group Careers, accessed July 17, 2025, https://careers.lanesgroup.com/resources/women-engineering-2025-key-trends-and-future-opportunities

- 50k Diverse Engineers Graduating Annually by 2025, accessed July 17, 2025, https://50kcoalition.org/

- www.wepan.org, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.wepan.org/strategic/50k-coalition#:~:text=The%2050K%20Coalition%20is%20a,engineering%20graduates%20annually%20by%202025.

- February 11: International Day of Women and Girls in STEM – OFCE.Sciences-Po.fr, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.ofce.sciences-po.fr/blog2024/en/2025/20250227_MB/

- Engineering and technology workforce – May 2025 update – EngineeringUK, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.engineeringuk.com/research-and-insights/our-research-and-evaluation-reports/engineering-and-technology-workforce-may-2025-update/

- IEEE-USA: Strengthening the Stance of Women in Engineering, accessed July 17, 2025, https://ieeeusa.org/ieee-usa-strengthening-the-stance-of-women-in-engineering/

- Women in Engineering and STEM: A Review of the 2024 Literature – SWE, accessed July 17, 2025, https://swe.org/magazine/women-in-engineering-and-stem-a-review-of-the-2024-literature/

- Tough trade-offs: How time and career choices shape the gender pay gap – McKinsey, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/tough-trade-offs-how-time-and-career-choices-shape-the-gender-pay-gap

- Women and STEM − A 2025 Update – Utah State University, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.usu.edu/uwlp/files/snapshot/58.pdf

- Women in Tech in 2025: 50+ Statistics Point to a “Bro” Culture – Spacelift, accessed July 17, 2025, https://spacelift.io/blog/women-in-tech-statistics

- Not a welcoming place. A new study sheds light on the situation of women scientists and engineers in the private sector, accessed July 17, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2572117/

- Exploring the Gender Gap: Women in STEM Today – GLOBAL SOUTHS HUB, accessed July 17, 2025, https://globalsouth.org/2025/03/exploring-the-gender-gap-women-in-stem-today/

- Women’s Reasons for Leaving the Engineering Field – Frontiers, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00875/full

- Gender Pay Gap Doubles in 2024: Women in STEM Paid 87 Cents For Every Dollar Men Earn – Staffing Hub, accessed July 17, 2025, https://staffinghub.com/press-releases/gender-pay-gap-doubles-in-2024-women-in-stem-paid-87-cents-for-every-dollar-men-earn/

- Gender Pay Gap Statistics 2025: A Comprehensive Analysis, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.equalpaytoday.org/gender-pay-gap-statistics/

- Women’s earnings were 83.6 percent of men’s in 2023 – Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed July 17, 2025, https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2024/womens-earnings-were-83-6-percent-of-mens-in-2023.htm

Explore more articles and insights on: Women in STEM and Tech